Today, we continue and finish our simmering tour of the Big Valley straddling Nevada and California. This setting truly has it all, including one of the most clear and majestic celestial displays anywhere in the world!

Early Human History: Four Native American cultures are known to have lived in the area during the last 10,000 years (at least that long). The first known group, the Nevares Spring People, were hunter-gatherers who arrived in the area perhaps 9,000 years ago (about 7,000 BCE). At that time there were still small lakes in the region, as well as in neighboring Panamint Valley. The climate was also milder. Large game animals were plentiful. These animals denote the reason why humans migrated here. Like everywhere else in the world and throughout time, humans followed the herds for food and articles of clothing, systematically destroying most of the game. By 5,000 years ago (about 3,000 BCE), the Mesquite Flat People wandered into the region, at which time the Nevares Spring People may have already moved elsewhere since the area now hosted fewer animal species. Around 2,000 years ago, the Saratoga Spring People wanted into the region.

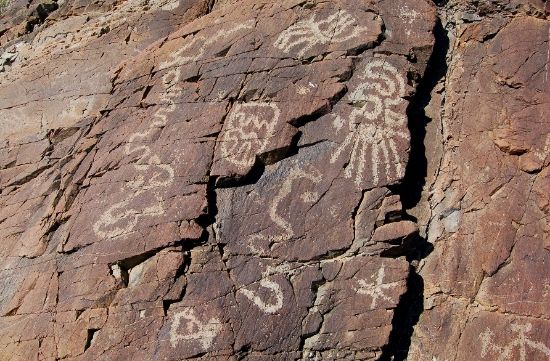

They, too, entered the valley, but this time their tribe adapted to a harsh climate that was probably already hot, dry desert. The reason is because their culture was a more advanced at hunter-gatherer society. They were also skillful at handcrafts. We know these people by mysterious stone patterns in the valley that were left when they finally moved on.

Nature's nutritional pantry––pinyon pine:

Some 1,000 years ago, the nomadic Timbisha (formerly called Shoshone; also known as Panamint or Koso) joined the short roster of nomadic emigrants to Death Valley. They hunted sparse wildlife and supplemented their diets with mesquite beans and piñon pine nuts, which are well known for their high caloric intake. Because of the wide altitude differential between valley bottom and mountain ridges, especially to the west, the Timbisha practiced a vertical migration pattern to sustain their presence here. Their winter camps were located near reliable water sources in the valley bottoms. As the spring and summer progressed and the weather warmed, they followed the grasses and other plant food sources that ripened at progressively higher altitudes. November found them at the very top of the mountain ridges where they harvested pine nuts before moving back to the valley bottom for winter.

The Next Wave: In time, this strange and beguiling territory was encroached upon by migrant Anglo during the California Gold Rush. In December 1849, two groups of California-bound Anglo travelers with perhaps 100 wagons found their way into Death Valley after getting lost on what they thought was a shortcut off the Old Spanish Trail. Called the Bennett-Arcane Party, they searched the valley but were unable to find a pass over the mountains for weeks. Fortunately, they did find fresh water at various springs and they survived by eating several of their oxen. They also used the wood of their wagons to cook the meat and make jerky. The place where these virtual pilgrims survived is today referred to as "Burned Wagons Camp," located near the sand dunes. After finally abandoning their wagons, they managed to hike out of the valley. The fable of the event claims that, just after leaving the region, one of the women in the group turned and said, Goodbye Death Valley, unofficially giving it the name by which we know it today. Included in this party was William Lewis Manly, whose autobiographical book, Death Valley in '49, detailed the trek and popularized the area. Geologists later named the prehistoric lake that once filled the valley after him.

After an unusual drenching during 2005's rainy season, the lake returned (a most unusual sight, indeed):

(Continues after the fold.)